For more than half a century, Donald McGill was the king of the naughty postcard market in Britain.

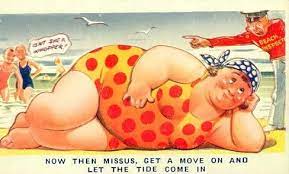

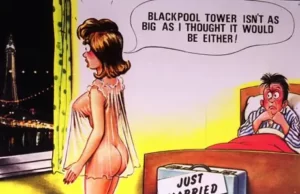

McGill’s mischievous paintings relied heavily on sexual innuendo to get a giggle from his customers. His stocks-in-trade were bulbous ladies on the beach, the illegitimate child, honeymoon couples, vicars with wandering eyes, and middle-aged male drunks with bright red noses.

The Art of Donald McGill

Donald McGill was born in London in 1875 and spent almost his entire life in the capital.

He stumbled into the occupation that made him famous in 1904 when he was developing a career in naval architecture.

A relative had seen an illustrated get-well card and suggested Donald draw one to send to his nephew, who was in hospital. His sketch showed a man up to his neck in an icy pond and had the caption, ‘Hope you get out soon.’

The cartoon was submitted to a publisher who commissioned more work, and he went on to design thousands of cards riddled with double-entendres ranging from the clever to the vulgar.

He classified the rudeness of his output as mild, medium, and strong. Of course, the strongest pictures were the ones that sold the best.

Prolific Postcard Artist

For six decades, Donald McGill dominated the seaside postcard business. He is estimated to have created 12,000 colour-washed drawings that sold somewhere in the region of 200 million copies.

In 1939, a million copies of McGill’s cards were sold by one Blackpool shop alone.

However, the artist did not profit greatly from his output; he sold his originals to publishers for a few pounds each and received no royalties from the sales bonanza that followed. When he died in 1962 at the age of 87, he left just £735, about £13,000 in today’s money.

Praise From George Orwell

George Orwell wrote about the work of Donald McGill and his imitators: ‘They are a genre of their own, specialising in very low humour, the mother-in-law, baby’s-nappy, policemen’s-boot type of joke, and distinguishable from all the other kinds by having no artistic pretensions. Some half-dozen publishing houses issue them, though the people who draw them seem not to be numerous at any one time.’

McGill Charged With Obscenity

An outbreak of prudery saw McGill facing charges under the Obscene Publication Act of 1857.

Often, naughty postcards had been banned from sale by puritanical forces, but their popularity remained strong. Then, after decades of selling his cards without any real problems, the law crashed down on Donald McGill like an anvil from the sky.

Police swooped on postcard vendors in the east coast resort of Cleethorpes. This was followed by raids to stop the selling of material deemed to be ‘corrupting the morals of the country’ hitting newsagents in other seaside communities. McGill was summoned to appear at the Lincoln Quarter Court in 1954.

It’s said his defence was going to be that he didn’t realise there was any double meaning in his cards, but he must have put that forward with a twinkle in his eye and his tongue in his cheek.

However, when his lawyer saw the composition of the jury, he advised McGill to plead guilty and take his medicine. The punishment was a fine of £50 and court costs of a further £25. The scandalous material was also removed from sale.

The War on Smut Ends

By the 1960s, the strait-laced bureaucrats that ran Britain’s censorship boards was in full retreat, and Donald McGill’s comic cards were back in the seaside shops, on the news-stands, and selling well.

But the end was near for the traditional British seaside holiday. Tour operators were starting to offer sun-starved Britons cheap hotels on Mediterranean beaches where even cheaper booze flowed like water. McGill’s art did not travel well to the sun-splashed coasts of Spain and Greece.

McGill himself, now well into his 80s, was also in decline, and he was producing only two new cards a week by the time he died.

He finally became respectable in 1994 when the Royal Mail put out a set of commemorative stamps featuring his images. The prestigious Tate Gallery in London has also displayed his art.

He never made much money from his work, but now his originals sell for thousands of pounds each today.